Recording-breaking carbon emissions in 2023 could be a sign that nature's carbon removal systems are failing, a study awaiting peer-review warns.

With last year's atmospheric CO2 growth going hand-in-hand with record heat, an international team of researchers found high temperatures are likely to have "had a strong negative impact" on the ability of land-based ecosystems to soak up carbon.

With ocean and land processes previously absorbing about half of all human-induced CO2 emissions, the possibility of such a significant decrease in capacity is a serious cause for concern.

"Nature has so far balanced our abuse," Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research director Johan Rockström said at a New York Climate Week event in September, as reported by Patrick Greenfield in The Guardian. "This is coming to an end."

Current climate models don't factor in the collapse of carbon sinks, potentially explaining why global warming is happening faster than predicted. Previous theories have ranged from miscalibrations in our modeling to a reduction in heat-reflecting aerosols resulting from changes in shipping regulations.

Tsinghua University ecologist Piyu Ke and colleague's preliminary findings suggest land-based sinks stalled in their carbon absorption, at least temporarily, during 2023.

They found that while CO2 emissions had only increased by around 0.6 percent since the previous year, the growth detected in the atmosphere over Mauna Loa station was a staggering 86 percent higher than 2022. Previous research found the ocean's ability to absorb our CO2 has been severely compromised too.

"This implies an unprecedented weakening of land and ocean sinks, and raises the question of where and why this reduction happened," the researchers explain.

The researchers calculated that all the CO2-hoovering land processes – from breathing trees and grasses to microbes tucking the problematic molecules down into the soil – took back almost no more carbon than natural land processes produced in the first place.

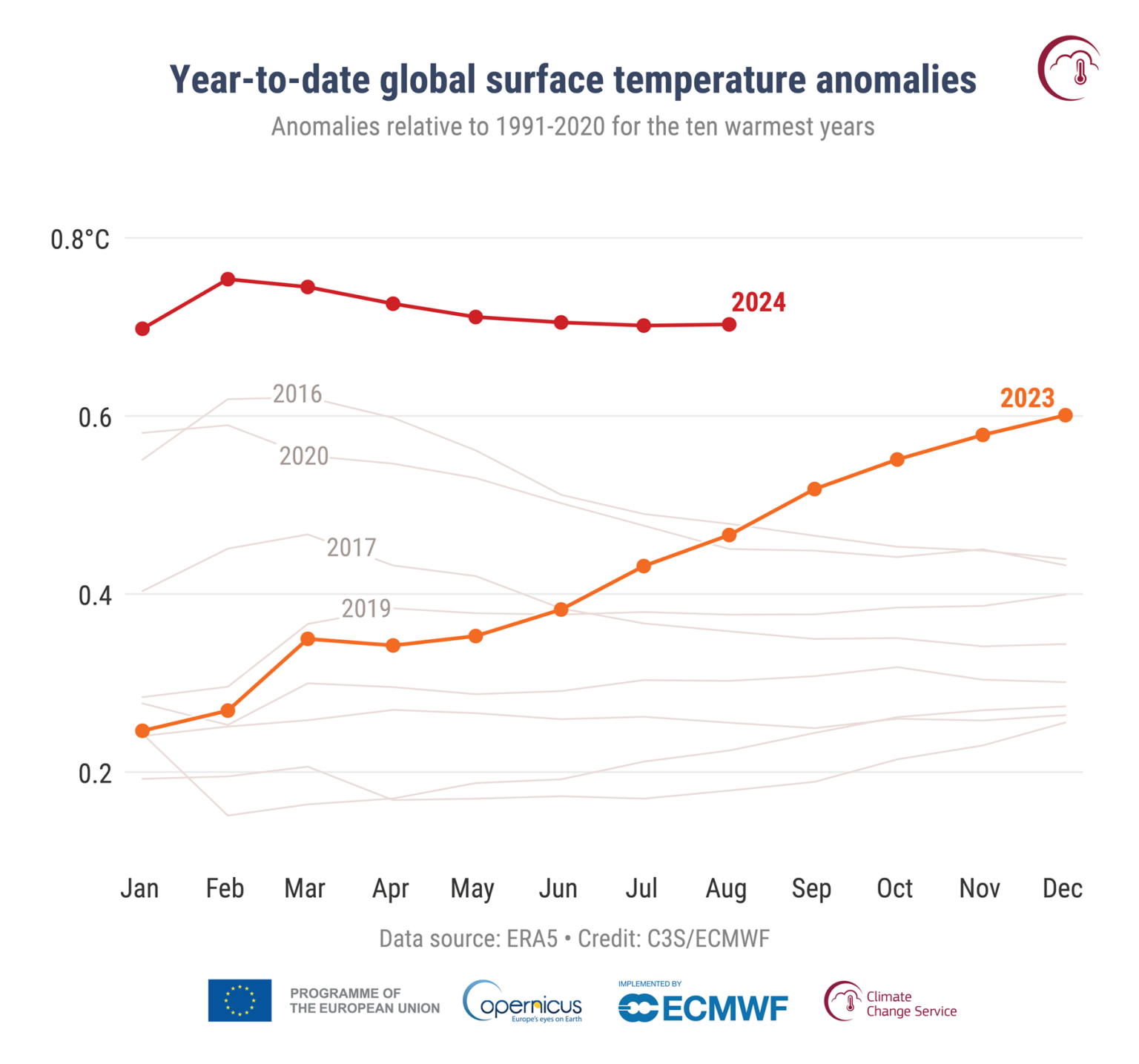

"This result is alarming as temperatures continue to keep very high values in 2024," Ke and colleagues write in their preprint.

The Amazon rainforest, which has been beleaguered for years by droughts and fires, contributed the largest drop in the annual global land sink.

If climate change-induced droughts and wildfires are primarily responsible for the loss of land-based carbon sinks, the problem may be a temporary one. The forecasted La Niña is expected to return precipitation to critical areas, making the researchers hopeful that carbon absorption may return to previous levels in coming years.

But a lot of the damage that has already occurred will be long term.

"Forests burned in Canada will not completely restore their carbon stocks for the next decades, given that it takes about 100 years for boral trees to recover their initial biomass," Ke and team explain.

Only the Congo basin seems to be drawing down more carbon than it produced in recent years.

With attempts to find solutions in technology still progressing, Earth's natural abilities to draw down carbon remain the only means of wide-scale carbon removal we have. Efforts to try and bolster nature's carbon sinks have so far been dismal, with large projects, even in wealthy countries, failing to achieve their goals.

This again drives home that the only sure way we have of actually turning things around at all is the same thing scientists have been begging us to do from the get go.

"We really, really have to tackle the big issue: fossil fuel emissions across all sectors," Exeter University meteorologist Pierre Friedlingstein told Patrick Greenfield at The Guardian.

This research has been uploaded to arXiv and is awaiting peer review.