A series of savage lurches from intensely dry to fiercely wet conditions helped fuel the horrific winter fires we're currently watching destroy parts of Los Angeles and surrounding wilderness.

A new review of over 200 papers finds this 'hydroclimate whiplash' has increased considerably, most likely due to the atmosphere's rising capacity for absorbing and retaining moisture. And as our climate rapidly approaches 3 degrees Celsius of warming, these flood and fire instigating swings are expected to double in frequency.

In a dark coincidence, the researchers point to California's current catastrophe as a timely example of their recently published findings.

"In that publication, fairly incredibly, we use the example of a transition from anomalously wet to anomalously dry conditions in California being an example of the tangible consequences of hydroclimate whiplash," climate scientist Daniel Swain from University of California, Los Angeles, said in a livestream address.

"The consequences, from a wildfire perspective, are eerily, uncomfortably close to what has actually transpired this week."

As the atmosphere warms, its ability to absorb, hold, and release water increases, the researchers explain. Research from as far back as the early 19th century has found this atmospheric sponge capacity increases by about 7 percent for each degree Celsius of warming.

The "Expanding Atmospheric Sponge" Effect conveys consequences of air's increasing water vapor-holding capacity: Not only can larger sponge yield more water if saturated (& wrung), but its absorptive capacity increases *even if there's no water to absorb.* www.nature.com/artic…

[image or embed]

— Daniel Swain (@weatherwest.bsky.social) Jan 10, 2025 at 9:05 AM

The increased retention of water means that even if the overall amount of precipitation in a location stays the same, the ecosystem will become dryer. Rainfall in turn generates a vegetation boom, which dries out, creating the perfect recipe for increasingly intense wildfires.

"This whiplash sequence in California has increased fire risk twofold," explains Swain; "first, by greatly increasing the growth of flammable grass and brush in the months leading up to fire season, and then by drying it out to exceptionally high levels with the extreme dryness and warmth that followed."

Then, all that's needed to create a wildfire hellscape is a spark – something that's also being provided more frequently by nature now too. A higher frequency of lightning strikes is another consequence of the climate catastrophe, with about a 12 percent increase of strikes predicted for every degree rise of global average temperature.

This is what ignited many of Australia's black summer fires in 2019, another example in Swain and colleague's paper.

What's more, shifts in the timing of dry and wet periods within this deadly cycle are also causing complications, which exacerbated the dangerous conditions in Los Angeles.

" Climate change is increasing the overlap between extremely dry vegetation conditions later in the season and the occurrence of these wind events," says Swain. "This, ultimately, is the key climate change connection to Southern California wildfires."

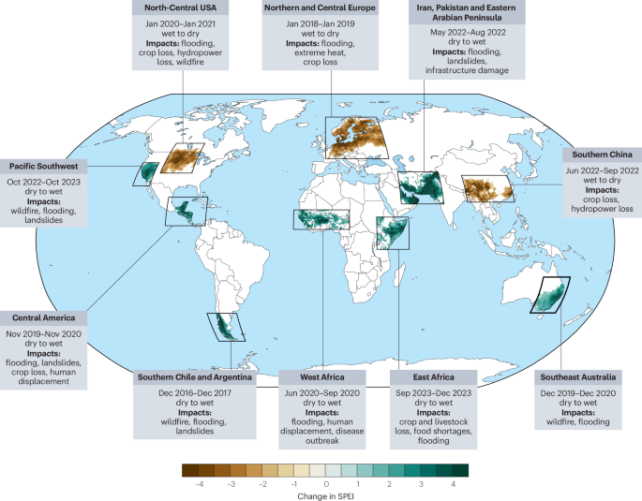

The whiplash can cause just as much havoc in the other direction too, the researchers highlight, providing East Africa's deadly 2023 dry to wet swing as an example. After years of drought reduced the soil's ability to absorb water, torrential rains in the midst of harvest season generated massive floods in Somalia, Ethiopia, and Kenya.

The deluge killed hundreds of people, destroyed thousands of hectares of crops, and displaced 2 million people.

How are consequences of hydroclimate volatility different from wet and dry extremes (e.g., floods & droughts) in isolation? Well, sometimes the temporal sequencing matters a great deal for widely ranging reasons, from public health to geohazards. www.nature.com/artic…

[image or embed]

— Daniel Swain (@weatherwest.bsky.social) Jan 11, 2025 at 11:19 AM

Using weather records, Swain and colleagues found hydroclimate whiplash has increased from 31 percent to 66 percent since around the 1950s, and is continuing to rise at an exponential rate.

"Hydroclimatic volatility is anticipated to further increase in magnitude, and to emerge robustly in additional regions as a consequence of anthropogenic climate change," the team warns.

The only way to slow this down is to do the one thing researchers have been begging our leaders to do for decades now: reduce fossil fuel emissions. The cost of continued failure to do so is killing people and wildlife across continents. The impacts are now starkly recorded in the scorched ruins of one of western civilization's most iconic cities.

This research was published in Nature Reviews.